You’re looking at a bag of raw, green coffee beans from Bean of Coffee. They seem inert, like little brown pebbles. But inside each one is a locked treasure chest of chemical compounds—hundreds of them—waiting to be transformed by roasting into the complex flavors of your morning brew. For a business owner focused on quality control, like Ron, understanding this composition isn't academic; it's the key to predicting roast behavior, troubleshooting flavor issues, and truly appreciating why sourcing from a farm that prioritizes bean health matters so much.

So, what is the chemical composition of a raw coffee bean? In short, it’s a sophisticated package of carbohydrates, proteins, acids, lipids, and minerals. The exact ratios of these compounds, shaped by the variety (like our Yunnan Arabica or Catimor), terroir, and processing, determine everything from the bean's density to its potential for sweetness, acidity, and body. At Bean of Coffee, we view our green beans not just as a product, but as a biochemical promise—one that our farming and processing practices are designed to optimize.

Let's open this treasure chest and explore the major chemical families that make coffee so much more than just a caffeine delivery system.

What are the carbohydrates and polysaccharides in green coffee?

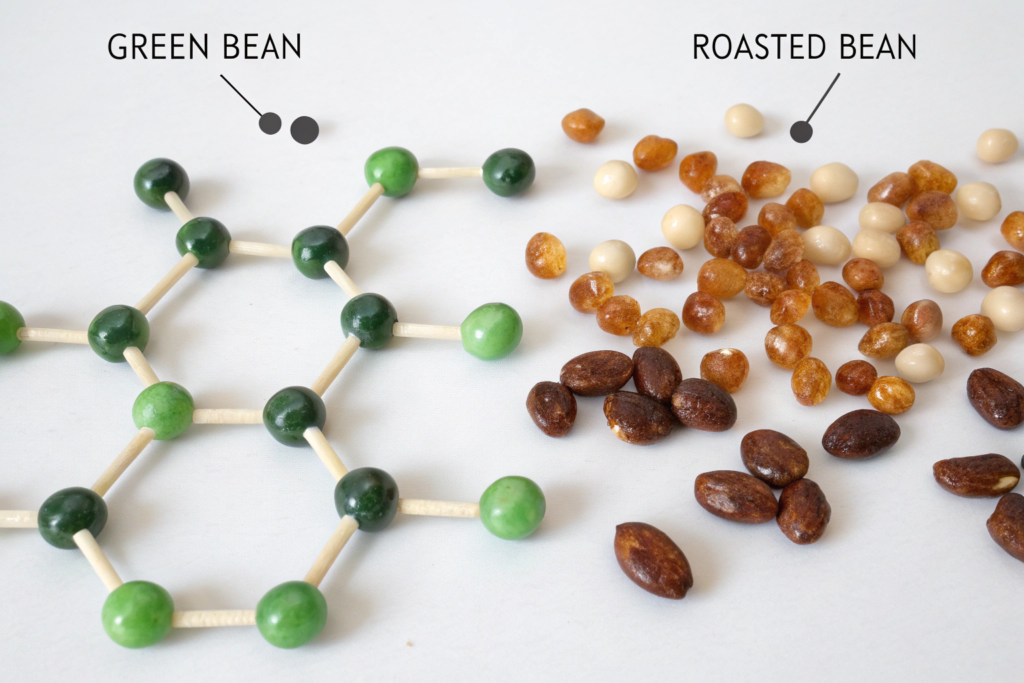

This is the biggest group, making up about 50-60% of a green coffee bean's dry weight. But these aren't simple sugars ready for your tongue; they're primarily complex, insoluble carbohydrates like cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin—the stuff that forms the bean's physical structure.

Think of them as the bean's architectural framework. During roasting, these complex chains break down through pyrolysis. Some transform into simpler, sweet-tasting sugars (like sucrose, which is present in small amounts initially), while others caramelize to produce the brown color and many of the rich, malty, and toasty flavors we associate with coffee. The quantity and structure of these carbohydrates influence the bean's density and how it transmits heat during roasting.

How does sucrose content affect flavor potential?

Sucrose is the primary simple sugar in green coffee, typically comprising 6-9% of its weight. This is the flavor gold. During roasting, sucrose caramelizes and participates in Maillard reactions (with amino acids) to generate a vast array of flavor and aroma compounds.

A higher sucrose content generally means greater potential for sweetness and complexity in the cup. Factors that boost sucrose include:

- Arabica vs. Robusta: Arabica beans (like ours) contain almost twice the sucrose of Robusta.

- High-Altitude Growth: Slower cherry development at altitude allows more sugar accumulation.

- Ripe Harvesting: Beans from fully ripe cherries are richer in sugars. This is why our selective picking at Bean of Coffee is a non-negotiable quality step. A bean's sucrose level is a direct report card on its growing conditions.

What is the role of polysaccharides in body and mouthfeel?

While they don't taste sweet, polysaccharides like cellulose and hemicellulose are critical for body (mouthfeel). During brewing, some of these large molecules dissolve or swell, contributing to the viscosity and the silky, creamy texture of the coffee.

The way a bean is processed can affect these structures. For example, natural (dry) processed beans often yield a coffee with heavier body, partly because some fruit sugars and pectins migrate into the bean during drying, adding to the polysaccharide complexity. The integrity of these structures is why proper drying and storage are so vital—if beans get damp, polysaccharides can break down prematurely, leading to a thin, papery cup.

What are the acids, lipids, and proteins?

Beyond carbohydrates, three other families play starring roles: acids provide vibrancy (and potential problems), lipids carry aroma and create mouthfeel, and proteins are the essential partners in creating flavor.

The balance between these groups is what separates a flat, dull coffee from a vibrant, complex one. It's also what makes coffee so sensitive to how it's grown and processed.

How do chlorogenic acids and others influence taste?

Green coffee is surprisingly acidic. The most significant group are Chlorogenic Acids (CGAs), which can make up 5-10% of the dry weight. In their raw form, they taste bitter and astringent.

Here's the magic of roasting: CGAs break down into other compounds, including quinides (some associated with bitterness) and caffeic acid. The degree of breakdown significantly impacts flavor. A light roast retains more CGAs, which can contribute to perceived brightness alongside fruity acids. A darker roast breaks down more CGAs, reducing acidity but potentially increasing bitterness from the breakdown products. Other acids like citric, malic, and tartaric (found in much smaller amounts) are the direct sources of fruity, wine-like acidity in the cup. Their levels are heavily influenced by variety and climate.

Why are lipids (coffee oils) so important?

Often called coffee oil, lipids account for 12-18% of an Arabica bean's weight (Robusta has less). They are mostly locked inside the bean's cellular structure in green coffee.

Their role is multifaceted:

- Aroma Carriers: Many of coffee's volatile aromatic compounds are oil-soluble. The lipids trap and then release these aromas during grinding and brewing.

- Mouthfeel: Extracted lipids contribute to the full, creamy, velvety sensation of coffee, especially in espresso where they form the prized crema.

- Freshness Buffer: The oil layer helps protect the bean from oxygen staling. As coffee ages, these oils can oxidize and become rancid. The high lipid content of Arabica is one reason it's prized for its complexity but also why it has a shorter shelf life than Robusta.

What is the role of proteins and amino acids?

Proteins make up about 10-13% of the green bean. While they don't directly flavor the coffee, they are the indispensable fuel for the Maillard Reaction during roasting.

In this complex reaction, amino acids (the building blocks of proteins) react with reducing sugars (like sucrose) to produce hundreds of Melanoidins. These large, brown-colored compounds are responsible for:

- The brown color of roasted coffee.

- Much of the coffee's body and mouthfeel.

- A range of savory, roasty, and bready flavors.

The specific profile of amino acids in the bean, influenced by its variety and nutrition, helps determine the unique flavor outcome of the roast.

What about caffeine, trigonelline, and minerals?

These are the minor but mighty components. Caffeine is the most famous, but its two companions—trigonelline and minerals—are equally important in shaping the cup.

How much caffeine is really in a green bean?

Caffeine is a natural alkaloid and pesticide for the coffee plant. Its content varies:

- Robusta: 2.2-2.7%

- Arabica: 1.2-1.5%

So, while Bean of Coffee's Arabica has less caffeine, it's chosen for its superior flavor complexity. Caffeine itself is bitter and tasteless. Its contribution is more about perceived "strength" and the physiological effect than direct flavor. Roasting reduces caffeine content only very slightly.

What is trigonelline and why does it matter?

Trigonelline is another alkaloid, comprising about 0.5-1% of the green bean. It's heat-sensitive and largely breaks down during roasting into two important groups:

- Pyridines: Contribute to the earthy, roasty, and nutty aromas of coffee.

- Nicotinic Acid (Vitamin B3/Niacin): This is why coffee is a dietary source of niacin.

The degradation of trigonelline is a key indicator of roast degree. More degradation means a darker roast and a different aromatic profile.

What do minerals (ash) contribute?

Minerals like potassium, magnesium, and calcium make up about 3-4% of the bean, measured as ash after complete burning. They act as flavor modifiers and affect extractability.

They influence the bean's electrical conductivity and how it interacts with water during brewing. The mineral profile, shaped by the soil of the farm (like the volcanic soils in parts of Yunnan), can subtly influence the perception of acidity and sweetness. It's a direct link from the earth to your cup.

Conclusion

A raw coffee bean is a masterpiece of natural biochemistry. It is a structured matrix of carbohydrates (for body and sweetness potential), acids (for vibrancy), lipids (for aroma and mouthfeel), and proteins (for flavor development via the Maillard reaction), all seasoned with active alkaloids like caffeine and trigonelline. The precise proportions of these compounds are a fingerprint of the bean's variety, origin, and care in cultivation and processing.

Understanding this composition shifts your perspective. It explains why a high-altitude Arabica tastes different from a lowland Robusta, why roasting transforms bitterness into complexity, and why sourcing from a farm dedicated to bean health—like Bean of Coffee—is the first and most critical step in the flavor journey.

Ready to explore the chemical potential locked in our beans? The journey from biochemistry to flavor begins with a sample. Contact our export manager, Cathy Cai, at cathy@beanofcoffee.com to request green bean samples of our Yunnan Arabica or Catimor. Discover how the right composition in the raw bean lays the foundation for an exceptional roast.